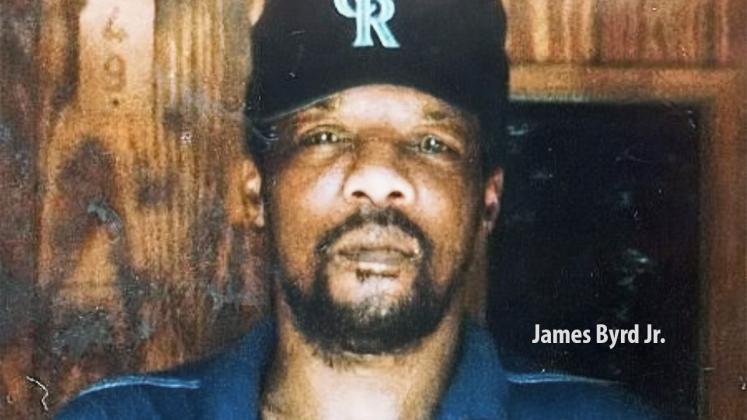

On a Sunday morning 25 years ago, a human body was discovered on Huff Creek Road in Jasper County. The next morning, a local newspaper first reported that “Jasper authorities were investigating the death of a man in Jasper.” It was a short news story that wasn’t even printed on the front page.

It was the general public’s first glimpse at what would become one of America’s most dominant news stories at the end of the 20th Century. It would change many of us, especially those of us who were in some way associated with the James Byrd Jr. murder case.

Case background

Early Sunday morning, June 7, l998, Jasper County law enforcement authorities were alerted that a passerby on Huff Creek Road had seen the most disturbing sight of a mangled human body lying on the road. It was James Byrd Jr.

He was decapitated and his right arm was missing. Severe friction burns were evident over his body. His knees, toes and heels were ground down. Deep gashes were evident on his lower legs and just above his ankles. A dark line left from the friction burning of Byrd’s body with road pavement was evident down Huff Creek Road for over three miles.

Local authorities quickly determined a most horrifying event had occurred.

They requested Federal authorities to assist them. Shortly afterward, I was urgently called into the office of Mike Bradford, the United States Attorney for the Eastern District of Texas. I was the Criminal Division Chief for the District’s 93 counties. U.S. Attorney General Reno was on his phone. She told us, “Something terrible has happened in Jasper. Get the FBI and go help those people see that justice is done.”

With those marching orders, a coalition of federal, state and local authorities would work together tirelessly and committed to thoroughly investigating, preparing, and prosecuting those responsible.

Byrd’s death

The investigation proved that three individuals were involved and ultimately charged with Byrd’s death: John King, Lawrence Brewer and Shawn Berry.

The investigation showed they were riding in a light blue pickup truck and picked up Byrd after midnight as he was walking home along Martin Luther King Road in Jasper.

A young man coming home late about to unlock his front door saw the truck pass by with James Byrd sitting in the truck’s bed and three white men in the cab. Although he was just a few blocks from his home, Byrd was instead taken by the three men down Huff Creek Road.

They turned onto a dirt road for about one-half mile to a clearing in the woods. Byrd was overpowered. Authorities discovered beer bottles and cigarette butts at the clearing which was later connected by DNA testing to the defendants. Also retrieved from the clearing were the defendants’ tools and a lighter, as well as other items indicating Byrd must have been fighting for his life.

A logging chain was taken from the back of the truck which the defendants wrapped around Byrd’s ankles. He was then dragged behind the truck down the dirt road and then onto the asphalt of Huff Creek Road.

The truck weaved back and forth along Huff Creek Road as Byrd struggled to stay alive. The medical examiner testified at the defendants’ trials that he was alive and struggling until his body struck a driveway culvert about a mile-and-a-half down Huff Creek Road, which decapitated him.

The medical examiner testified that Byrd suffered excruciating injuries. What remained of his body was then dragged another mile and a-half and abandoned on Huff Creek Road at the county’s edge near the gate of a cemetery. Along the road, personal effects of Byrd were found, including his keys and dentures. DNA testing from the 3-mile dark stain left on Huff Creek Road positively matched to Byrd.

Authorities quickly connected the evidence to King, Brewer and Berry, who were staying together in Jasper. They were taken into custody and questioned. Berry gave several statements blaming King and Brewer for Byrd’s death.

A search of their apartment resulted in the recovery of evidence connecting them to the crime including three sets of shoes showing traces of Byrd’s blood.

This crime and related events shook the world. The Ku Klux Klan visited Jasper twice, shortly after Byrd’s murder. The New Black Panther Party also came to town to protest against the Klan.

We prayed for hard rain for each event. Fortunately, most of the observers were law enforcement officials and members of the press. Those who were present heard hate-filled, vulgar, and ignorant rhetoric from those groups. Most people either ignored them or attended peace and prayer meetings held at other locations.

Before the trials, the press discovered that a cemetery in town contained a fence which had long-separated the graves of deceased whites and blacks. Even though there were attempts to characterize this city as a town full of bias, it became readily apparent that Jasper was predominantly made up of good and peace-loving people.

Trials

King, Brewer and Berry were indicted in Jasper County State Court for capital murder. The U.S. Attorney’s Office worked together with the Jasper County District Attorney’s Office in preparing and prosecuting the case. Contrary to what many believed, it would not be easy to convict the three defendants. This case was based exclusively on circumstantial evidence since there were no witnesses to the actual dragging of Byrd.

Through intensive and tireless efforts, authorities collected evidence connecting the three defendants to the crime with DNA matching. Compelling evidence included jail notes between King and Brewer which were intercepted while they were in custody awaiting trial reflecting they took some perverse pride in being charged with the crime.

Over 100 people were interviewed in the investigation. About 60 witnesses would testify in each trial. We were able to show the relationship of the three defendants with each other, and their actions before, during, and after the murder. Authorities even found the chain which dragged James Byrd to his death and which was buried in the woods.

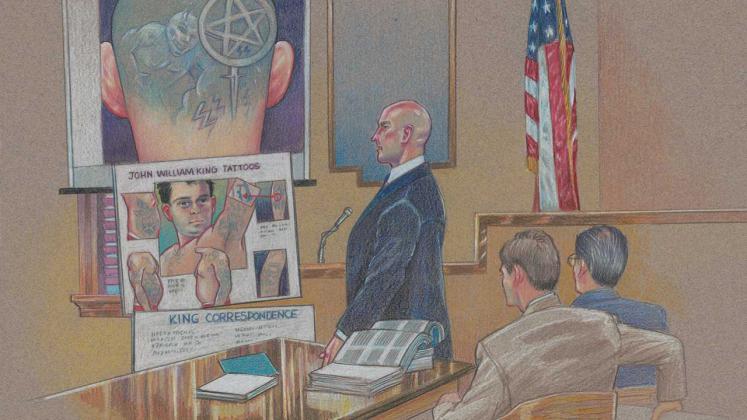

King’s trial was first, occurring in Jasper, in January and February 1999. King appeared bored and did not testify during the five-week trial. The jury of 11 whites and one black took two-and-a-half hours to find him guilty and another two-and-a-half hours to decide he deserved the death penalty.

In August and September 1999, Brewer’s trial took place in Bryan, Brazos County. Similar evidence was presented but in this case Brewer testified that only King and Berry killed Byrd. In its investigation, the FBI and I went to Huntsville and searched the archives of all confiscated prison contraband seized in the Texas prisons.

There, we discovered several documents connecting Brewer to White Supremacy groups. One item admitted at his trial was a signed oath with his bloody thumb print pledging “swift and merciless justice” to enemies of his race. The all-white jury did not show Brewer mercy and he was also given the death penalty.

Berry was tried later in Jasper. He was convicted and received life imprisonment, probably because of his youth and lack of connection to hate groups.

The trials of King and Brewer showed them to be connected to a hate group called the Texas Rebel Soldiers, connected with the Confederate Knights of America of the Ku Klux Klan. It was apparent from the beginning of this investigation that racial hatred was the motivating force of the crime.

Hate crimes

Emergence of hate crimes or bias crimes in America.

The term “hate crime,” also referred to as “bias crime,” has made its way into contemporary American culture beginning in the mid-1980s. The terms apparently were first publicly used in the 1985 Congressional House Bill called the “Hate Crime Statistics Act.” The term “hate crime” made its first magazine appearance in a 1989 article in U.S. News and World Report, discussing a District of Columbia punishment enhancement statute.

Legal scholars and writers began frequently using the terms in the early 1990s. In 1985, there were only 11 referrals to “hate crimes” in the nexus national media database, but by 1990 there were more than 1,000. For 1999, there were more than 15,000 such referrals. Hate crime and bias crime are routinely used today to refer to crimes motivated by prejudice against the victims’ characteristics such as race, religion or sexual orientation.

Not long after the Byrd murder, on Oct. 12, 1998, Matthew Shepard died from a smashed skull after he was beaten five days earlier near Laramie, Wyoming. He was left lashed to a fence for 18 hours in subfreezing temperatures. This ruthless assault was motivated by Shepard’s homosexuality. Aaron McKinney, 22, and Russell Henderson, 21, of Laramie, were convicted of the murder. Each received two consecutive life sentences.

Also, about the times of the Byrd and Shepard murders, on Feb. 19, 1999, Billy Jack Gaither, of Alabama, had his throat slashed and was beaten to death. His body was then burned on a pile of old tires. Gaither, a homosexual, was killed because of his sexual orientation.

Steven Mullins, 25, and Charles Butler, 21, were charged with Gaither’s murder. Mullins had a reputation for wearing shirts with KKK on them. Both were sentenced to life imprisonment without parole.

Byrd’s murder was one of 13 hate-motivated murders of 1998 in the United States. It was one of almost 8,000 reported bias-motivated criminal incidents that year. President Bill Clinton expressed a sense of grief and outrage at the tragic and violent deaths of Gaither, Shepard and Byrd. Calling the murders heinous and cowardly crimes, the President stated those acts of hatred defy the values of decency our society holds most dear.

In the 25 years since Byrd’s death, there have been bias-motivated incidents reported at a rate of about one every hour. There were 9,000 hate crimes reported in the U.S. for 2021. Texas reported 500 of these.

The effects of hate and violence threaten our social fabric. It is like a virus which lurks in the body of our great nation which must be exposed and combated. It is an age-old, man-made problem requiring man-made solutions. Purveyors of hate must be exposed and punished severely when they commit hate-motivated crimes.

Lesson learned

From time to time we are all tested. How we respond to challenges is the true test of character. Hate and hate crimes are problems for all of us. It is a matter of “good versus evil.” The overwhelming majority of people are caring and peaceful, and are intolerant of Hate Crimes, but evil triumphs when good people do nothing.

Robert F. Kennedy observed: “Every time someone stands up for an ideal, or acts to improve the lives of others, or strikes against injustice, a ripple of hope is sent. Those ripples can collect together into a mighty wave which sweeps away the sturdiest walls of oppression and resistance.”

When hate crimes occur they must be dealt with expediently and firmly. The investigations must be thorough and professionally accomplished. The trials must be handled with integrity and fairness.

Currently, many states and the federal government have instituted laws which enhance or increase the punishment range of crimes motivated by hate as with the Texas’ James Byrd Hate Crime Act of 2001. Also, the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act of 2009 expanded federal sanctions for those victimized because of their identity or orientation.

Authorities in the Byrd case were motivated by the confidence and support of the courageous Byrd family as well as by our oaths to “Preserve, Protect and Defend the Constitution, our Laws, and our People.”

We were inspired by the cruel death of a person most of us had never met. A simple, yet talented American citizen. A man loved by his family and friends, and whose pain and suffering in death we felt as fellow Americans and human beings.

“E pluribus unum” is the Latin phrase found on the Great Seal of the United States which is our country’s motto and national emblem. It means “Out of Many, One.” Out of many people, races, and ancestries we are a melting pot of Americans, unified in a brotherhood of citizenship. Out of many, one unified voice of condemnation of this hate crime came forth. One unified spirit, seeking and finding justice under the law, emerged.

Conclusion

We must constantly strive to ensure that our Creator’s gift to us of life, liberty and happiness are not just ideals, but real deals; and that the Blessings of Liberty are shared by all of us, and protected for our children to enjoy.

Let us all remember that God’s work on Earth is truly manifested by and through each of us, living America’s ideals. Martin Luther King stated: “Let us pray that the dark clouds of racial prejudice will soon pass away, and in the not too distant tomorrow, the radiant stars of love and brotherhood will shine over us with all their scintillating beauty.”

That cemetery fence which long separated the graves of whites and blacks in Jasper was pulled down.

Justice and peace overcame hate in Jasper.

From 1979 to 1981, John B. Stevens Jr. was assitant district attorney in Jefferson County. Afterwards, he was associate attorney with Provost & Humphrey, LLP, and assistant distrcit attorney, and assistant U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Texas from 1985 to 2005.

Stevens currently serves as the longtime elected Judge of the Jefferson County Criminal District Court.

For the 20th anniversary of Byrd’s death, the family foundation placed a memorial bench outside the Jasper County Courthouse with the quote: “Be the change you wish to see in the world.”

As part of the 25th year of remembrance, the Byrd family requested that the city proclaim June 7, 2023, as James Byrd Jr. Day during the June 12 City Council meeting.

By John B. Stevens Jr.

Guest Editorial

Special to The Examiner